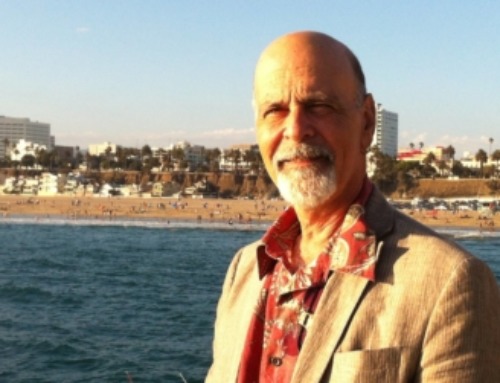

Review by Howard Shrier

Review by Howard Shrier

National Post, April 24, 2017

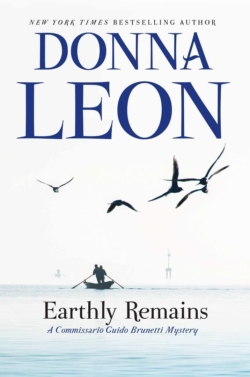

It’s been 25 years since Commissario Guido Brunetti entered the world of crime fiction. And what an entrance it was.

“Because this was Venice, the police came by boat.”

With just nine words, Donna Leon showed she could set a scene and tell a story without getting in her own way, hardly something one takes for granted. Her Commissario, the star detective of Venice’s Questura, knew when to listen and when to listen even harder, searching for the truth behind and in between words.

From the start, Leon flaunted conventions of crime fiction – was the murder in that first novel, Death at La Fenice, even a murder? – and thrived on ambiguities from which most beginners might have shrunk.

Fans of her work will be delighted to know that her 26th book, Earthly Remains, continues that tradition, as the Commissario investigates a death that was most likely an accident but could also have been suicide, given the victim’s frame of mind. Murder never quite enters the equation.

Very little happens, in fact, but in the right hands, much can be made from nothing.

In a nutshell – and the plot fits rather easily into one – Brunetti commits an act in the workplace that suggests he is ripe for a few weeks of stress leave. That he did it to protect his young colleague Puccetti is immaterial, because Brunetti does in fact need to get away. His ethics take a beating at the hands of his long-time nemesis, the self-important Vice-Questore Giuseppe Patta. The political compromises he must make eat away at him.

With Venice stifling in a heat wave, he heads for the island of Sant’ Erasmo, where he spent summers as a youth, planning to row by day and read Pliny’s Natural History by night. One of his wife Paola’s many wealthy relatives owns a villa there and the elderly custodian, Davide, is a highly skilled rower who once won a regatta with Brunetti’s father.

A friendship of sorts forms as Brunetti regains his rowing skills under the older man’s tutelage. But the custodian often seems disturbed, rambling to himself or his dead wife, and his back is marked by strange red scars. As they row around the island, they inspect beehives that Davide set up in his retirement, only to find many of the queens dying, the colonies collapsing around them, and the old man’s mood grows darker.

After Davide goes missing during a storm, Brunetti finds his body submerged with his capsized boat, a rope coiled tight around one leg. Most likely an accident, but Brunetti – and Davide’s daughter – wonder whether Davide might have wanted to die. He had been heartbroken and lonely since his wife died of cancer a few years earlier, and he seemed haunted by the accident that scarred him so badly years before. He took the death of his bees terribly hard.

The matter is not Brunetti’s to solve; it’s not clear there is anything to solve. But like so many enduring heroes, he lives by his own code. Though not hard-boiled in a traditional sense, he could not sound more like Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe when he explains why he has to understand Davide’s death: “I never had the sense I knew him except that he was a decent, honourable man and now it pains me that he’s dead…. I’m sorry if that doesn’t sound like much.” *

Brunetti enlists a few trusted colleagues – Sergente Lorenzo Vianello, computer whiz Signorina Elletra and detective Claudia Griffoni – to help him conduct an unofficial investigation. He wants to know why Davide was visiting a woman on nearby Burano when he was so loyal to his dead wife. Why one of his co-workers, with similar livid scars, lives in a retirement villa that costs a hundred thousand euros a year.

In My Venice and Other Essays, Leon, the one-time mystery critic at the London Sunday Times, wrote that while novels of the Golden Age generally featured individual murderers who went about their business chastely, newer novels encompassed larger social ills and crimes. Of those thinking of writing a crime novel, she asked: “Will the resolution implicate one guilty party or will a larger social or political group be implicated?”

The beauty of Earthly Remains is that it weaves true mystery out of ambiguity. Guilt is left to the eye of the beholder. On the surface, this crime novel might not contain an actual crime, yet it is clear that many a line has been crossed, that the people involved did regrettable things they thought they had to do to survive.

Having lived in Venice for well over 30 years, Leon knows her world intimately, yet never overloads the reader with research. She shows only the tip of her iceberg, confident in the richness that lurks underneath. The cast is small but memorable. The square miles she covers are few but exploding with life – at least where humans have yet to quash it.

Not one shot is fired in Earthly Remains; not one punch is thrown. But Leon is no softie. She shows the pounding Venice takes from tourism, pollution and its own bureaucrats. Her eye is sharp and unsentimental, whether roaming through the hot, grimy city, a cold autopsy room, or lagoons so poisoned, even the tides around them no longer make sense.

More importantly, she takes the reader deep into the discontented soul of a detective whose work these days leaves him feeling as Pliny must have when Vesuvius erupted and packed his lungs with ash.