National Post, January 16, 2017

American historian Caleb Carr created a stir with his 1994 novel The Alienist. Set in New York City in 1896, the novel mixed historical characters such as then-Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt with the fictional Dr. Laszlo Kreizler, a pioneer in criminal psychology.

Helped by reporter John Moore, Kreizler profiled the fiend killing and mutilating young male prostitutes. He kills according to a timetable; his victims represent something created in his troubled early years; he taunts the authorities; he wants to be caught.

These by now are clichés to anyone who has read about serial killers, but they were shocking revelations in 1896, just eight years after the Ripper killings. That Carr’s narration was often overwrought and ungainly seemed consistent with the late Victorian setting.

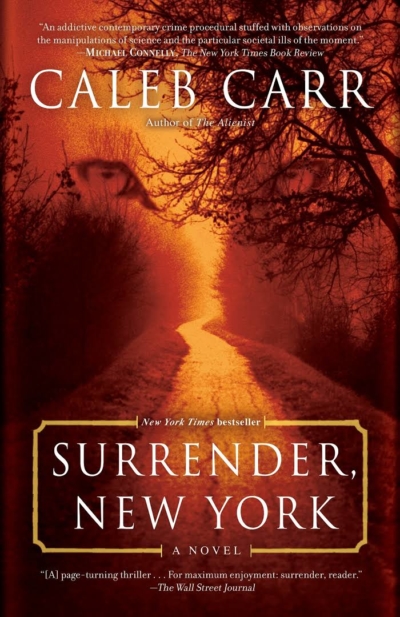

Carr’s new novel, Surrender, New York, introduces Dr. Trajan Jones, a distinguished criminal scientist, disciple of Kreizler and advocate of his theories on investigation. Jones and his partner, Mike Li, a leading expert in trace evidence, once worked in Manhattan but left after too many dust-ups with authorities, and now live and work upstate near the town of Surrender.

When a young local girl is found dead in what is either an overly elaborate suicide or a painstakingly staged murder, the local sheriff knows he’s in over his head either way, because two other young victims have been found the same way. Not trusting the state crime bureau, he asks Jones and Li for help.

The partners discover that the victims had all been abandoned by addicted or deadbeat parents, and posit a provocative new theory: that they were lured away by wealthy predators in New York City, were used and tossed away, and then did in fact kill themselves after being abandoned by the state. Jones and Li also believe the governor knows about this but wants it kept secret until after the next election.

This aspect – the heartbreaking lives of “throwaway” children and the search for their seducers – might have made for a gripping 350-page thriller. But this 592-page opus is sunk by narrative bloat, the author’s persistent devotion to pet causes and his need to explain the history of every car, telephone and dry-erase board Jones comes across.

Jones is supposed to be brilliant, but who wouldn’t be next to the idiots who make up his opposition? The M.E. is a clown, the lab tech is both corrupt and inept, two key witnesses manage to get shot right before talking, the killer confesses everything just when a cop is listening outside the door…

Jones is less a person than a collection of crime-fiction tics. He walks with a limp (Kreizler had a withered arm), lives with his fierce great-aunt (Moore lived with his grandmother), keeps a pet cheetah, works in the fuselage of a World War I bomber, packs a 1911 model Colt, drives a vintage Crown Vic he calls The Empress and can instantly recognize a Bottega Veneta hobo bag, Alexander McQueen jacket and Anne Fontaine shirt.

This is research, not writing – and it continues throughout. A historian first and a novelist second, Carr can detail a minor character’s history back to Iroquois days but never bring him alive. He can’t call a character Latrell without devoting a full page to the basketball player who inspired the name. This, along with the stilted narrative voice, drags Surrender’s pace to a crawl. It takes Jones and Li two pages to get down a driveway and six to find a body in a basement. A trip to New York City, first conceived in chapter two, is still in the planning stages 300 pages later.

Carr also mounts Jones on one soapbox after another, saving particular scorn for people who abuse big cats and the writers of TV shows like CSI who sometimes skew facts to tell stories. But soapboxes don’t make good building blocks. And if TV writers sometimes get their facts wrong, they often get character and dialogue right. Would that Carr could do so: the relentless banter between Jones and Li is supposed to be funny but barely makes juvenile. And Carr’s characters are one-dimensional props, there to serve transparent narrative purposes.

Got two lonely bachelors working upstate, one Asian, one not? Carr drops in lovely matches for both. Need to remind your reader just how brilliant Jones is? Bring in a dumb New York City reporter he one-ups in a laughably implausible scrum. Want a young sidekick for the boys? Introduce Lucas Kurtz, the abandoned 15-year-old who has access to a computer but never uses it, neither wants nor has a cell phone and has read every Sherlock Holmes story ever written (right).

If you care deeply about Carr’s causes or enjoy listening to awkward men insult each other ad nauseum, this might be the book for you. I’d rather watch a rerun of CSI, where one can see real humanity in the grieving relatives, bewildered witnesses, damaged killers and the CSIs themselves.

Surrender? Not to this.