The Globe and Mail asked me to contribute an essay about the challenges of writing a second book. The following was posted on Globe Online Tuesday, Oct. 6, 2009.

My first novel, Buffalo Jump, took four years to complete, from the first notes scribbled on the back of an envelope to the final manuscript accepted by Random House Canada. Four years of researching, outlining, writing, knock-’em-down and tear-’em-up revisions, fussing, fretting, buffing, polishing, editing, i-dotting and t-crossing.

And then, in a moment of madness the likes of which Charles Manson probably never imagined, even while carving a swastika in his forehead, I told my prospective publishers I only needed a year to write the second.

This was at the Bier Bistro in Toronto, where my agent Helen Heller and I were having lunch with the publishers of Random House and Vintage Canada, Anne Collins and Marion Garner.

They told me how much they liked Buffalo Jump, a mystery featuring a young Toronto investigator named Jonah Geller who teams up with a reluctant hit man to prevent the slaughter of a local family. Then Anne said, “Do you have a second book on the go?”

I said I did: a sequel that brought back most of the characters from the first book. The plot, I said, revolved around construction and development in Toronto’s port lands. That’s as much as I told them—because that’s about all I knew at that point.

“When do you think you’ll have a draft ready?” Anne asked.

Feeling my oats, or perhaps the Belgian beer, I replied: “When would you like it?”

Anne explained that many mystery writers opt for being book-a-year writers, while others issue one every eighteen months to two years. (Never mind Jeffrey Deaver, Nora Roberts and Robert B. Parker, who somehow write two or three a year.)

“A book a year,” I said. “That’s me.” I meant it too. I’d been writing professionally for some 25 years at that point. Starting as a journalist, with stops in television, sketch comedy, improv and corporate communications, I’d always been known as a fast, sometimes furious writer.

I wrote High Chicago in one year in my office atop the Victory Cafe

Maybe because a book deal seemed achingly close—or maybe God was just punishing this Jew for ordering the pulled pork sandwich—the fact that Buffalo Jump had taken four years to finish seemed to have slipped my mind.

Granted, I had been holding a full-time job in communications the first three of those years, working on the book in the early mornings, evenings, weekends, holidays and subway rides. I’d since left the job to finish Buffalo Jump and now had nothing but time on my hands. Twenty-four hours a day to spend on the sequel. I even had an office of my own, a bright room above a café in the Annex near Honest Ed’s.

Piece of cake, right?

More like a cake of soap under my feet.

There was a reason Buffalo Jump took so long to write. Yes, I worked quickly when it came to news writing and corporate work. What I had forgotten, in my pork-induced haze, was that fiction is decidedly different. I have always needed incubation time when writing fiction, going back to my earliest short stories. I have to read and research and absorb information and let it all sit and stew until ideas start to bubble. And no amount of pressure, self-induced or otherwise, can rush that process. With Buffalo Jump, I’d been working entirely on my own schedule. I made notes for a solid year before I entered the first line of text into my computer. I worked for 18 months on the first draft, another 14 on the second.

Granted, I knew my characters much better when I started High Chicago. Had honed my craft over those four years. Had received excellent reviews and an offer to option the characters for a proposed TV series. All of which buoyed my confidence but amounted to precisely squat when it came to writing the second book.

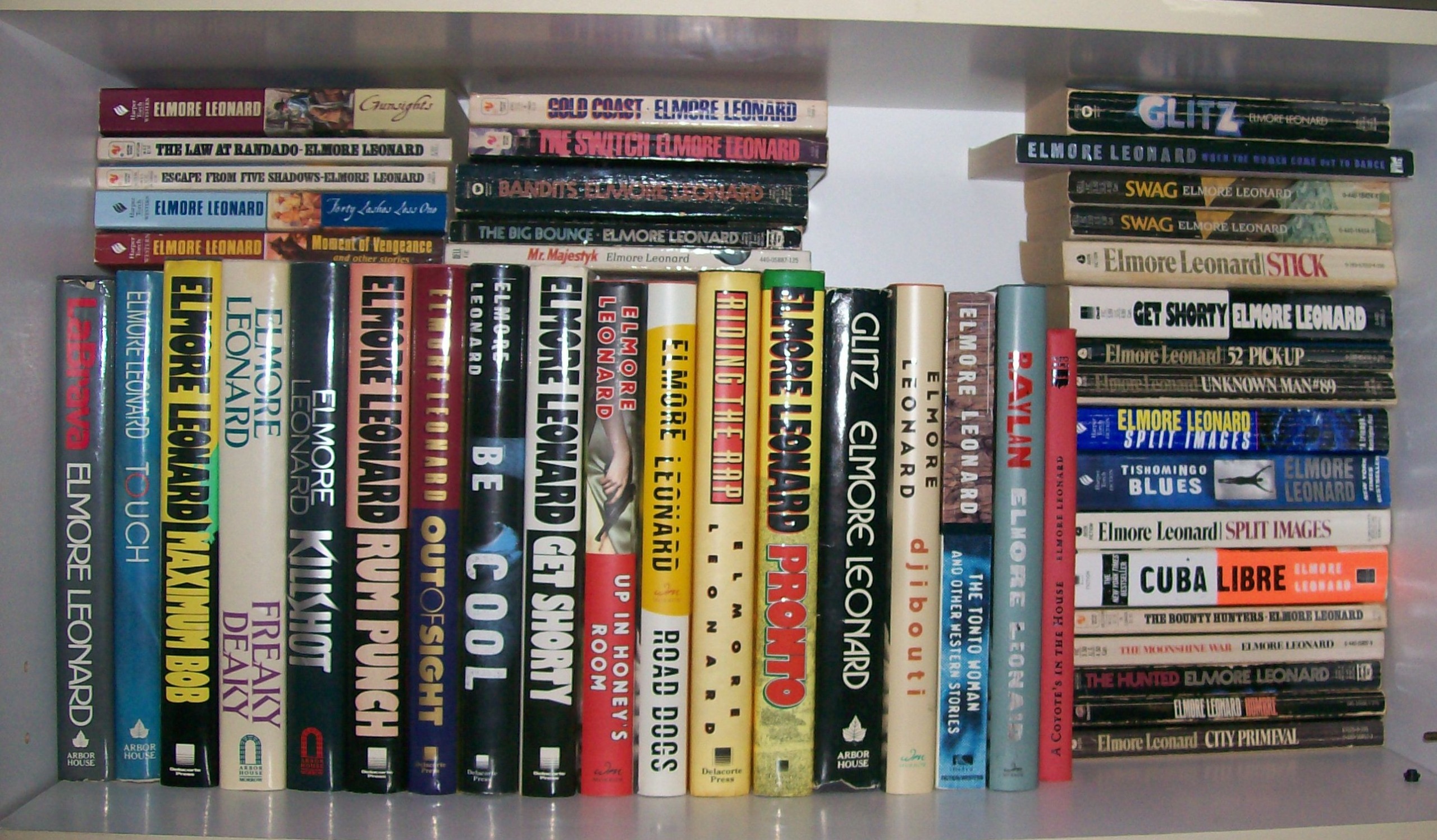

And so I sat in my newly acquired office, surrounded by my library of crime books. I read and researched matters related to building skyscrapers. Watched the new Trump tower in Chicago go up via Webcam. I furrowed my brow, cracked my knuckles, kneaded my neck muscles and waited, as one sportswriter put it so eloquently, for beads of blood to appear on my forehead. I implored a God I don’t believe in. I learned the joys and agonies of online poker. I haunted Book City, Sonic Boom, BMV Books and assorted Thai restaurants on my stretch of Bloor Street.

What I didn’t do was write. I didn’t even make notes, as I had done with Buffalo Jump, three 200-page notebooks worth. I let it all swirl around in my head like the laundry of the damned. Weeks and months drifted by. I wrote a grand total of two chapters and then junked them. The walls closed in, like the set of a German Impressionist film: The Office of Howie Caligari.

And then, some seven months into the process, it happened. I started to hear Jonah’s voice again (both books are told in first person). I think enough time had passed to let the organic process take root. The subconscious had done its percolating thing. The story had been building all this time. It was time to move the surveyors out and let the construction workers in.

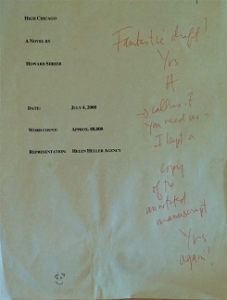

One of my proudest moments was getting this reaction from my great editor, Anne Collins.

Five months later, I completed the first draft. Not only that, it was a damned good draft. My agent, a tremendous editor who knocked down Buffalo Jump more often than the young Mike Tyson knocked down his opponents, basically sent it on to Random House untouched. And Anne Collins, a brilliant editor who had her work cut out for her on Buffalo Jump, hardly got to use her red pen on it.

Just a few months later, the final copy-edited manuscript of High Chicago was on its way. I had made my deadline and the book came out in July, 13 months after its predecessor. I was a book-a-year guy.

So now I’m working on book three. It’s taking forever. I’m only halfway through the first draft and there seems no way in hell I’ll make the deadline to get it out in summer 2010.

On the plus side, I won an 18-person online Texas Hold ’Em tournament yesterday, pocketing $14.20 on a $2.25 buy-in. Which is probably more than Jeffrey Deaver can say.

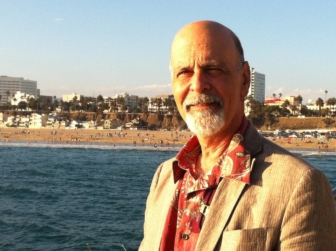

Howard Shrier’s debut thriller, Buffalo Jump, won the Crime Writers of Canada’s Arthur Ellis Award for the Best First Novel of 2008. A native Montrealer, he now lives in Toronto with his wife and two sons.