Readers who enjoy hard-boiled detective novels with expert pacing and rich physical details will delight in Miss Montreal, the fourth from Toronto-based novelist Howard Shrier. Those who also hold the city of Montreal dear – potholes and all – will be in heaven.

The story begins in late June. Toronto-based private investigator Jonah Geller has been hired to probe a murder case on which the Montreal police can’t – or won’t – make progress. “Slammin’” Sammy Adler, a widely read columnist at Montreal Moment magazine, has been found beaten to death, a Star of David carved into his chest. Is it a random act of anti-Semitism? Was it a targeted crime? Sammy’s grandfather, widowed and dying, wants answers and hires Jonah to get them.

Jonah takes his work seriously, but this case has an added personal dimension: he knew Sammy, albeit decades ago. When the two boys attended summer camp together, Jonah took the gawky Sammy under his wing and coached him on what became a “slammin’” baseball swing.

Equipped with high-tech surveillance gear, plenty of ammunition, and a dry sense of humour, Jonah and his sidekick, a gun-loving bruiser called Dante Ryan (Jonah’s regular partner Jenn is recovering from something that happened in a previous book), zoom up the 401 to Montreal and are immediately immersed in the city’s charms: gorgeous women, smug cops, crowded terrasses, French-language stalwarts, and rutted roads. As they dig into the stories Sammy was researching at the time of his death, they uncover a web of crime, violence, xenophobia, political ambition, and long-buried family secrets.

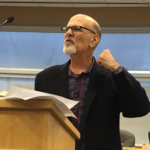

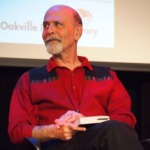

“Shrier is a two-time Arthur Ellis Award

winner and it’s easy to see why.”

Howard Shrier is a two-time Arthur Ellis Award winner and it’s easy to see why. Miss Montreal offers exciting action sequences, realistic dialogue, wry wit, an airtight plot that unfolds with perfect pacing, and bedroom scenes that are sexy without being smutty. His characters are so real that this reviewer felt genuine anxiety over using the term “side- kick” in the previous paragraph lest the goon read it and take offense.

But Montrealers may find that the most impressive part of the book is Shrier’s portrayal of their city. The description of Montreal from the perspective of an outsider – our overabundance of Saint-named streets, our aggressive driving – is super. The explanations of how heavily accented French is pronounced (“boîtes – boxes – pronounced bwytes. Place sounded like plowce”) are bang on. The references to recent events, including chunks of concrete falling from overpasses and the ongoing Charbonneau investigation, are apt. And the irritation that Jonas and Dante feel when faced with characters who are staunchly anti-English is palpable. The scene in which a meathead French-Canadian cop refuses to speak with Jonas and Dante in English (Dante retaliates by speaking Italian, including calling the cop a few choice names that cannot be reprinted here) is deliciously satisfying to any Montrealer who is frustrated by the recent resurgence of linguistic prejudice in the province.

The only place the story drags is in the first few chapters when Shrier refers to events that occurred in his previous novels. But this is a necessary part of writing a detective series. New readers must be given some context and old readers must be rewarded for coming back to the trough, and the combination of the two makes for uneven storytelling.

In the acknowledgement, Shrier states, “writing crime fiction is a dream come true.” Keep writing books like this, Howard, and the pleasure will be all ours. — Sarah Lolley, Montreal Review of Books