The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud

The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud

My grandparents all fled Czarist Russia in the 1920s. This classic novel from 1966 helped me understand why. A poor handyman named Yakov, whose wife has deserted him after six years of childless, turbulent marriage, leaves his village to seek a better life in Kiev, capital of Ukraine. But he finds the city a hotbed of vile anti-Semitism, with strict rules as to where a Jew can work or live. A chance encounter with a wealthy Russian gives Yakov the opportunity to lift himself out of poverty and earn a decent living—if he can hide the fact that he is Jewish. He carries it off for a while. But when a Russian child is found murdered, stabbed and bled white, the authorities seek out a Jew to blame and Yakov’s world collapses around him. Reminiscent of Kafka’s The Trial, The Fixer richly portrays the bleak life Yakov leads in and out of prison.

Idiots First, by Bernard Malamud

A great book of stories by a master. About half are set in the art world of Rome, while the others are mostly in the world of poor Jewish merchants in New York. Malamud sometimes writes in the vein of the great Isaac Bashevis Singer, but always brings his own style and verve to his work. He is best known for his novels The Natural, The Assistant, The Go-Between and The Fixer, but I remain fond of the stories in this collection and The Magic Barrel. [Full disclosure: Malamud was the writing teacher of my writing teacher, Clark Blaise, so I sometimes feel a special connection to him, as if we were very distant relatives.]

Granite City, Dying Light, Dark Blood, and Flesh House, all by Stuart MacBride

Many readers of crime fiction will argue that some of the best work these days is coming out of Scotland. I couldn’t agree more. I’ve always enjoyed the work of Christopher Brookmyre, Denise Mina and Ian Rankin. Now comes Stuart MacBride and his series featuring DS Logan McRae of the Grampian Police Force in bloody Aberdeen. The series comes flying out of the gate in Granite City, with McRae back on the job after a year on medical leave, after suffering horrific near-death injuries at the hands of a serial killer. He is plunged straight into a number of cases that stretch him and the force to the limit. The books I have read so far are densely plotted, the writing veers from hysterically funny to incredibly dark and gruesome, the characters are rich and real and the swearing alone is worth the price of admission. Aberdeen, as rendered by MacBride, is cold, wet and as miserable as its ill-tempered residents. Read them in order if you can. But read them. This is Tartan Noir at its best.

Many readers of crime fiction will argue that some of the best work these days is coming out of Scotland. I couldn’t agree more. I’ve always enjoyed the work of Christopher Brookmyre, Denise Mina and Ian Rankin. Now comes Stuart MacBride and his series featuring DS Logan McRae of the Grampian Police Force in bloody Aberdeen. The series comes flying out of the gate in Granite City, with McRae back on the job after a year on medical leave, after suffering horrific near-death injuries at the hands of a serial killer. He is plunged straight into a number of cases that stretch him and the force to the limit. The books I have read so far are densely plotted, the writing veers from hysterically funny to incredibly dark and gruesome, the characters are rich and real and the swearing alone is worth the price of admission. Aberdeen, as rendered by MacBride, is cold, wet and as miserable as its ill-tempered residents. Read them in order if you can. But read them. This is Tartan Noir at its best.

Prague Fatale, Phillip Kerr

As much as I have enjoyed the Bernie Gunther novels in the past, I am close to giving up on this series. Prague Fatale is something of a locked room mystery set in a castle outside Prague where Reinhard Heydrich and other senior Nazis are housed, consolidating their hold over Bohemia and Moravia, as Czechoslovakia was known to them. Gunther is there as bodyguard to Heydrich, following threats to assassinate him. When one of Heydrich’s adjutants, a promising young captain, is found shot to death, Bernie is ordered to investigate. Though Kerr’s research is impeccable as always, I found the novel disjointed and structurally weak. I think Bernie’s best days were back in the Berlin Noir trilogy, especially when he was a private investigator at the Adlon Hotel.

Freedomland, by Richard Price

Never officially tabbed as a crime writer, Richard Price (Clockers, Lush Life, Samaritan) nonetheless writes some of the best crime fiction I’ve ever read, and Freedomland is quite possibly his best. It’s a harrowing, beautifully written story of a young woman, Brenda Martin, who stumbles onto the grounds of a bleak housing project in New Jersey, claiming a black man hijacked her car while her four-year-old son slept in the back seat. As the hunt for the child escalates, the police surge through the project looking for suspects. Tempers flare, the media descend in hordes, racism abounds and the sweltering heat drives people wild. Às he works the case, Detective Lorenzo Council doubts Brenda’s story but can’t get to the truth; reporter Jesse Haus manages to befriend Brenda, trying to get the story while retaining her humanity. The tension just keeps rising as angry protesters fight the police and a full-scale riot seems the only possible outcome. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Steve Jobs, by Walter Isaacson

Was Steve Jobs a visionary, a genius, an artist of the highest order… or a tantrum-throwing, credit-stealing, limelight-hogging control freak from hell? The answer is yes and yes, according to Isaacson. The portrait he paints of Jobs includes plenty of warts–he could easily have been the worst person in history to work for, a man without any filters whatsoever when it came to shaming and berating anyone who didn’t meet his exacting and ever-changing standards. Put up for adoption by his birth parents when they were 23, he abandoned the out-of-wedlock daughter he fathered at 23. This is just one of the dozens of contradictions that made up the man, but there is no denying the influence he had on computers, music, animated films and design.

Civilization, by Niall Ferguson

The British historian puts forth an interesting premise: around 1500 C.E., Europe, Asia and the Ottoman Empire were roughly equal in terms of knowledge, influence and sovcial development. In the ensuing five centuries, Europe went on a tear, surpassing its rivals in every way. Ferguson suggests it was able to do so because of six “killer apps”: science, the rule of law, medicine, private property, work ethic and competition. Chapters devoted to each are impressively detailed and supportive — I can only wish I were half as well read. The conclusion is somewhat sombre: that the West has lost much of its edge and is in the throes of losing what’s left. A great read.

The Spinoza of Market Street by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Every once in a while, I like to read something completely outside my usual range of crime and other fiction. These stories, by the Nobel prize winner Isaac B. Singer, originally written in Yiddish, bring to life the fools, sages, rich men, poor men, servants and masters of the lost world of European Jewry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Singer creates a fantastic setting where people are haunted by real demons and imps (The Destruction of Kreshev is narrated by Satan himself) as well as their own weaknesses and foibles. Singer writes with great tenderness for his subjects while exposing their carnality, greed and other flaws.

Four Revisionist Westerns by Pete Dexter, Charles Portis, Elmore Leonard and Patrick DeWitt

Deadwood by Pete Dexter

Though not the basis of the TV series Deadwood, I’d be surprised if creator David Milch never read Dexter’s 1986 novel of the same name. Like Milch, Dexter brings to life a very different Wild Bill Hickock than the hero we’ve seen in many a western film: he’s old, sick and tired of violence. The rest of the cast is similar to the series, featuring Wild Bill’s companion Charlie Utter, Calamity Jane, Al Swearingen, Seth Bullock and Solomon Star, though the roles they play are rather different than on the show. The prose is spare, without as much of the hilarious profanity Ian McShane and other TV characters spouted. But there is something vital about this novel from the author of the more acclaimed Paris Trout that made it well worth the read.

True Grit by Charles Portis

True Grit is also spare and funny, and if you’ve seen both film adaptations, it is much closer to the Coen brothers’ 2010 version than the one that featured John Wayne. It would in fact be unfair to call the Coen Brothers version a remake; they went back to Portis’s novel and stayed truer to the events than did the 1969 film. It was a quick read and I loved the feel of the dialogue, which hovers between the plain talk of Rooster Cogburn and Mattie Ross’s more elevated schoolmarmish narration.

The Sisters Brothers, by Patrick deWitt

The Sisters Brothers, by Patrick deWitt

Worth all the accolades and prizes it has garnered. In spare, moving prose, DeWitt spins the story of Charlie and Eli Sisters, feared killers for hire in the old West, who travel from Oregon to San Francisco in search of an inventor who has created a new means of finding gold. Eli, the narrator, is the gentler of the two–if gentle can be used to describe a hired gun–caught between the mission and his brother’s vile moods and binges. Unforgettable writing on every level.

Gunsights, by Elmore Leonard

Leonard started his career as a western writer: his novels Hombre and Valdez is Coming were both made into great films. In mid-career, around the time he wrote Swag, he returned to the genre to pen Gunsights, a yarn about a coming war over a copper mine, pitting the owners, including gunfighter Bren Early, against his old pal Dana Moon, who’s helping a band of Apaches, black families and Mexicans fight for their right to stay on the mountain. As newspapermen gather in the town of Sweetmary, arguing over what to call the anticipated conflict and laying bets on who is likely to survive, the stakes keep escalating until Early has to make up his mind whose side he is on. The writing is more expansive, colourful and cynical than the early westerns, and introduces two characters–Katie Moon and Bo Catlett–whose descendants play key roles in later Leonard novels such as Glitz and Get Shorty.

Field Gray, by Philip Kerr

I’ve read all the Bernie Gunther novels in this great series set in Germany before, during and after WWII. This one is more sprawling than the others, a kind of remembrance of things past for Bernie as he languishes in American custody—first in New York, then in Germany—following his arrest in Cuba in 1954. Kerr jumps back and forth in time to incidents that tormented Bernie, including his role as part of the Paris occupation force and as a prisoner of war in Russia, all linked to the war criminal Erich Mielke. Growing to hate his American interrogators, he reveals episodes that took place in the thirties and forties, each crammed with dozens of key Nazi figures, most of them real. Bernie is allowed to resume contact with an old Berlin flame linked to Mielke, a woman whom he has helped over the years, now alone after failed affairs with American servicemen. The result is not up to the same standard as Kerr’s Berlin Noir trilogy or others that have followed in the series. I honestly grew weary of all the jumps and found it hard to keep track of every name and rank spelled out. I also didn’t find the love affair that convincing or compelling. I’ll keep reading the series but this one was overwhelmed by all the research and needed tapering to a sharper flame.

The Drop, by Michael Connelly

This latest Harry Bosch novel—and I’ve read them all—is a winner start to finish. Two very different cases weigh on Harry as he adjusts to life as a single dad of a teenager. One is the latest from the Open/Unsolved cold case squad, in which a DNA hit in a brutal slaying leads them to a man who was just eight years old at the time of the murder. Harry also catches a fresh case fraught with political bullshit, also known as High Jingo: the apparent suicide of the son of his longtime nemesis Irvin Irving, who either jumped, fell or was pushed from the top of L.A.’s fabled Chateau Marmont. There’s pressure from the chief to satisfy Irving, now a councilman seeking revenge on the department after his ouster, which puts a strain on Harry’s relationship with friend and former partner Kiz Rider, now a police bureaucrat. Connelly does his usual masterful job on every level and I tore through this one in a hurry.

Raylan, by Elmore Leonard

Raylan, by Elmore Leonard

How’s this for a horror story: my third Jonah Geller novel, Boston Cream, came out on January 30, 2012 — the same day as Raylan, by my idol Elmore Leonard — and both were at least in part about organ theft. Raylan is not so much a novel as three interconnected stories about U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens, the hero of the novels Pronto and Riding the Rap, and “Fire in the Hole,” the story that launched the hit TV series Justified. The stories feature the aforementioned organ theft ring, an arrogant and ruthless strip-mining company; and a hip young poker-playing college girl who may or may not rob banks on the side. It’s interesting to see Leonard bend reality to suit the TV show. Boyd Crowder died in the original story after being shot by Raylan. But actor Walton Goggins’ portrayal proved so popular in the pilot, they allowed him to survive. Boyd is back in this book, guarding the coal company’s killer executive, courting local beauty and former sister-in-law Ava, and generally getting in Raylan’s way. The dialogue is always sweet and spot on, as usual. It’s a different rhythm from the man whose best novels, set in Detroit and Miami, were known for their urban, jazzy sound. Here he pares down the mountain patois to its barest needs. No one ever says more than they have to. And Leonard can’t write anything uninteresting. How it hangs together as a “novel” doesn’t approach his best work, and I’ll leave it to readers to decide whether the instant love affair between the fortyish Raylan and the 23-year-old Jackie holds water. But I own everything Leonard has ever written, including his great Westerns, and I’ll continue to buy whatever he puts out.

Super Sad True Love Story, by Gary Shteyngart

Set in the near-future—one might say the too-near future—in Manhattan, Shteyngart weaves an incredible tale in a world where social media rule, people rarely speak to each other, and love is nearly impossible to express. Like his previous novels, Absurdistan and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, it is funny, moving and beautifully written.

The Amateurs, by Marcus Sakey

There’s a reason Sakey has been called the reigning prince of crime fiction. He is incredibly talented, disturbingly young and even good looking, which is why I secretly hate him. His prose is riveting, sometimes startling, and his characters finely drawn. This story of four friends who undertake a robbery for all the wrong reasons, only to wind up way over their heads in dark waters, is a great read, Also worth checking out is Scar Tissue, his recent collection of seven “stories of love and wounds.”

Hound of the Baskervilles and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Hound of the Baskervilles and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

I’ve been fascinated by crime fiction for more than 30 years, but never was a big fan of Sherlock Holmes. I’ve read most of the novels over the years, watched various adaptations on film and TV and certainly acknowledge his influence and importance in the history of the genre, but mostly maintained a polite relationship with the whole canon. Prepping for an online mystery workshop I’m teaching through the New York Times Knowledge Network, I downloaded these free to my Kobo and thoroughly enjoyed them. Hound of the Baskervilles will be a great example of setting, as Conan Doyle completely captures the moors in their haunting menace. I was surprised at how well Watson could carry a story in which Holmes is gone for long periods of time. The Memoirs include the introductions of Sherlock’s smarter brother Mycroft and his great nemesis Moriarty, whose criminal prowess absolutely delights Holmes, who relishes a case that will crown his Hall of Fame career. I read most of these eleven stories while flat on my back after a Boxing Day accident, and under the slight influence of Dilaudid, so their length perfectly matched my compromised attention span. A good Holmes book to have if you only have one.

The Reversal, by Michael Connelly

I had read The Lincoln Lawyer and The Fifth Witness but somehow missed this middle entry in the Mickey Haller series. It pairs Haller with his half brother Harry Bosch, in the story of the retrial of a man who spent 24 years in prison for abducting and murdering a 12-year-old girl, but who has been given a new trial when DNA evidence appears to exonerate him. Only Haller isn’t defending the man; he’s on the other side as a special prosecutor, with Bosch as his investigator. A compelling read, but not quite as good as the other two. Maybe because I read it on my Kobo, where you can’t tell when you’re getting to the end of a book, but I found the ending flat by Connelly’s high standards.

The Affair, by Lee Child

Another fine entry in the Jack Reacher series, this one takes place during Reacher’s final days in the U.S. Army–his last case as an MP and investigator. In a sense it’s a prequel to the very first Reacher novel, Killing Floor, ending just a few months and a few miles from the time and setting of that book.

Suicide Run, by Michael Connelly

Now that I’ve joined the 21st century and bought a Kobo, I downloaded this Michael Connelly collection of three Harry Bosch stories. The stories take place at different points in Bosch’s career, from the earlier days when he partnered with Jerry Edgar to his more recent pairing with Ignacio Ferrara. The middle story, Cielo Azul, brings in Terry McCaleb, the FBI profiler who is featured in Blood Work and A Darkness More than Light. I enjoyed all of them, especially One-Dollar Poker, but best of all was the four-chapter preview of the new Bosch novel, The Drop. Can’t wait till it comes out November 28.

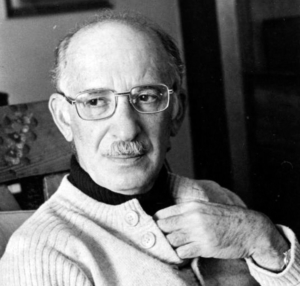

Oh Canada, Oh Quebec, by Mordecai Richler

And now for something completely different, Richler’s rollicking take on Quebec’s language laws and other political foibles, all part of my research for my fourth Jonah Geller novel, Miss Montreal.