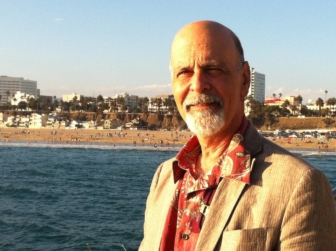

Review by Howard Shrier

Review by Howard Shrier

National Post, October 19, 2016

On a hot summer night in Atlanta – is there any other kind? – a pair of beat cops comes upon a minor car accident. The driver is clearly drunk, won’t show ID and the woman sitting beside him looks bruised. But the officers can’t arrest or even stop him because he is white and they are black – and the year is 1948. All they’re allowed to do is call for help. And what arrives proves far more dangerous than the man at the wheel could be.

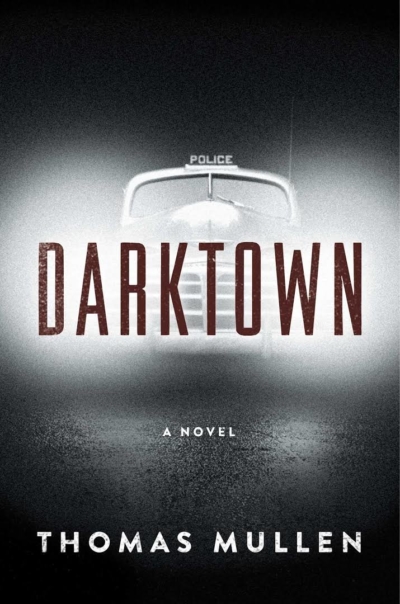

So begins Thomas Mullen’s brilliant new novel, Darktown, about the corrosive integration of the Atlanta Police Department, a force so racist that its union was dominated by Klan members until the mid-40s.

In the spring of 1948, after two years of pressure by black community leaders, the APD hired eight Negro Officers (black was a worse pejorative at the time). They were to patrol an area called “Darktown,” where moonshining, bootlegging and other crimes were expanding after the war – and white officers either ignored or exploited the action.

The first officers were frustrated at every turn. They couldn’t use squad cars or enter police headquarters. They worked out of the sweltering basement of the Negro YMCA. They were not allowed to investigate cases or “recklessly eyeball” white men. White officers made monkey noises when they saw them in the street. Other blacks thought they were doing too much or not enough.

It all boils over at the scene of that car accident, where four characters collide, two black and two white.

Negro Officer Lucius Boggs is a Morehouse College man, the son of a reverend, a register of voters, quick to insist a visitor not swear in his father’s house. Partner Tommy Smith is a fiery brawler and womanizer who won a Silver Star in the war, and remains restless for action of either kind.

Towering Lionel Dunlow, still a beat cop after 20 years, rules Darktown with his knuckles and nightstick. He’s a racist who tries to frame one Negro Officer for drinking – a firable offence – and falsely accuses Boggs and Smith of killing bootlegger Chandler Poe (nicely named for two founders of crime writing). When he comes upon a black man who’s been stabbed his response is to kick him where he’s cut. Dunlow’s new partner, a young war vet named Denny Rakestraw, is more moderate on race. He has no real animosity towards the Negro Officers; in fact, he’d rather patrol a white area than have to walk through Darktown with the skull-cracking Dunlow.

Boggs and Smith are helpless to act that night when Dunlow lets the drunk driver off. Or when the driver takes another swipe at his passenger and she escapes into the darkness. Her name is Lily Ellsworth, a light-skinned black from a country town called Peacedale, and she is shot to death later that night. When her body is found in a dump, Boggs knows he should have done more to help her but is forbidden to investigate – and a black victim stirs no interest in Homicide. His only hope is Rakestraw, and their awkward efforts to trust each other and solve the killing together drive Darktown up a menacing arc.

Mullen throws one obstacle after another into the path of his protagonists. Boggs risks a beating just for standing outside APD headquarters. A superior alters his reports; a judge treats him worse than the criminal he arrested. Boggs and Rakestraw face Dunlow`s increasing violence, the hatred of their contemporaries, the power of the congressman for whom she worked as a maid and a shady cabal of ex-cops who get called in to clean up APD messes. The drive to Peacedale, just 50 miles away, is so dangerous, it suggests to Boggs Heart of Darkness in reverse: black men making their way through the treacherous country of whites, the law resting solely in the hands of the nearest sheriff. Boggs makes the reference himself (he’s a Morehouse man, after all).

A native of Rhode Island who now lives in Atlanta, Mullen creates a brilliant setting, a sun-drenched city booming after the war, choking on its own unstoppable growth. He has won literary and historical awards for his first three novels, and shows both gifts in great supply here, such as his gut-wrenching narrative of a race riot that raged like a virus through Atlanta for three horrible days in 1906, or his description of a crop of peaches left large but tasteless as cotton after heavy rains and extreme heat, a brilliant metaphor of life for blacks in the Jim Crow South.

Too many crime stories are set in cities besieged by crime lords or (yawn) serial killers. In Darktown, Mullen stages a grim fight for Atlanta’s very soul, a clash between die-hard racists and moderates who know segregation must end. For the corrupt, dangerous Dunlow, who’s teaching his teenaged sons how to keep blacks out of their neighbourhood, every act of desegregation in his city or police force must be answered.

Not all whites are bad and not all blacks are good; Mullen’s characters are well shaded throughout. But all have long, deep Atlanta roots and want a say in its future and their subsequent clashes drive the story to its riveting end.

Is Darktown a great crime novel? Like many debuts in the genre, there are missteps – one late confrontation between Rakestraw and a suspect includes four maybes, one possibly and one I imagine – but they cannot detract from the novel’s power.

Set in 1948, with the Democratic National Conventional on the radio from Philadelphia – sound familiar? – the novel couldn’t be more contemporary in what it says about the need for more humane policing of African-American neighbourhoods. On grounds such as these were launched the earliest battle for civil rights.

I’m hoping there’s a series here – a sequel at least – which is the highest compliment I can pay.

Howard Shrier is a two-time winner of the Arthur Ellis Award for excellence in crime fiction. His novels include Buffalo Jump, High Chicago, Boston Cream and Miss Montreal. He teaches writing at U of T. Please visit howardshrier.com