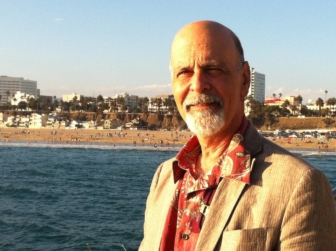

I was more than an avid fan of Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer series. Like many a crime writer I know, I consider him my greatest influence. Travelling in California in 1980, I decided to look up Macdonald in Santa Barbara. It didn’t work out quite the way that I planned as you’ll see in this memoir, published by Concordia University Magazine shortly after his death in 1983.

My friend Paul’s place off Hollywood Boulevard has no alarm clock, so I hump down to Santa Monica and the Motel Seven, where I pay double that for a single and a seven a.m. wakeup call. The night clerk, a Japanese man in his thirties, gives me the key and points to the second storey-walkway.

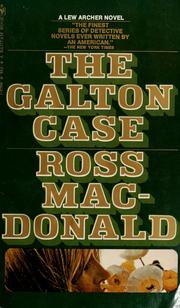

It is almost midnight and I want all the sleep I can get. I’ve dreamed for two years of tomorrow’s meeting. I lay my jeans over a blue vinyl armchair and reach deep into the underwear stash of my backpack for a clean pair. The bedside table is just big enough for wallet, cigarettes and my copy of Ross Macdonald’s The Galton Case.

***

When the Montreal Star folded late in 1979, the severance pay sent me to the islands and then the Mardi Gras. From New Orleans, 48 hours by bus on Highway 10, L.A. bound.

After checking into a West Hollywood motel, I flopped my bus-cramped body on the bed and phoned the Santa Barbara operator for Ross Macdonald’s number.

No such listing. There wouldn’t be; it was his pen name. I asked for Kenneth Millar, his real name. Yes, she said, on the Via Esperanza.

Macdonald was not a mystery writer. He was

a serious novelist who wrote about murders

and invented a detective to solve them.

I dialed the number. When a soft-spoken man answered (servant? secretary?), I asked if I might speak with Mr. Millar.

“This is he.”

Startled. Hadn’t expected him to be so easy to reach. My prepared speech sprouted wings and beat out into the mustard sky. I managed to burble out that I’d read every book he’d published and written a detective story* myself and I wanted very much to meet him if he could just spare the time or if he couldn’t, then could I send him my story and maybe he’d have comments but I’d really rather see him in person so we could talk to face because I’d read every book he’d published and really admired his work. . . .

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m very busy.”

An uncomfortable silence padded my long-distance bill.

“There is the writers’ lunch,” he finally said. “Students and writers are welcome. It’s here in Santa Barbara every two weeks.”

“When is the next one?”

“Two weeks from today.”

“I’ll rent a car and drive up.”

“It’s at El Cielito in La Arcada, near the museum.”

I jotted El Cielito, La Arcada, nr. Mus. in my notebook and thanked him. “See you in two weeks,” I added jovially.

***

Born Kenneth Millar, Macdonald spent most of his formative years in Ontario.

Now I lie in the Motel Seven, trying to sleep, but all the things I want to ask Ross Macdonald jangle in my head like construction bells.

I’ve wanted to meet him since I picked up one of six books my grandparents had saved in 35 years. Macdonald’s The Underground Man, the story of a man murdered while trying to locate his missing father. Against the backdrop of a California brush fire, a detective named Lew Archer scratched through a tangle of twisted relationships to uncover a second murder committed fifteen years earlier.

This was no vacation mystery. It had characters, prose and it rang from first page to last with the pain of living where and how his people lived.

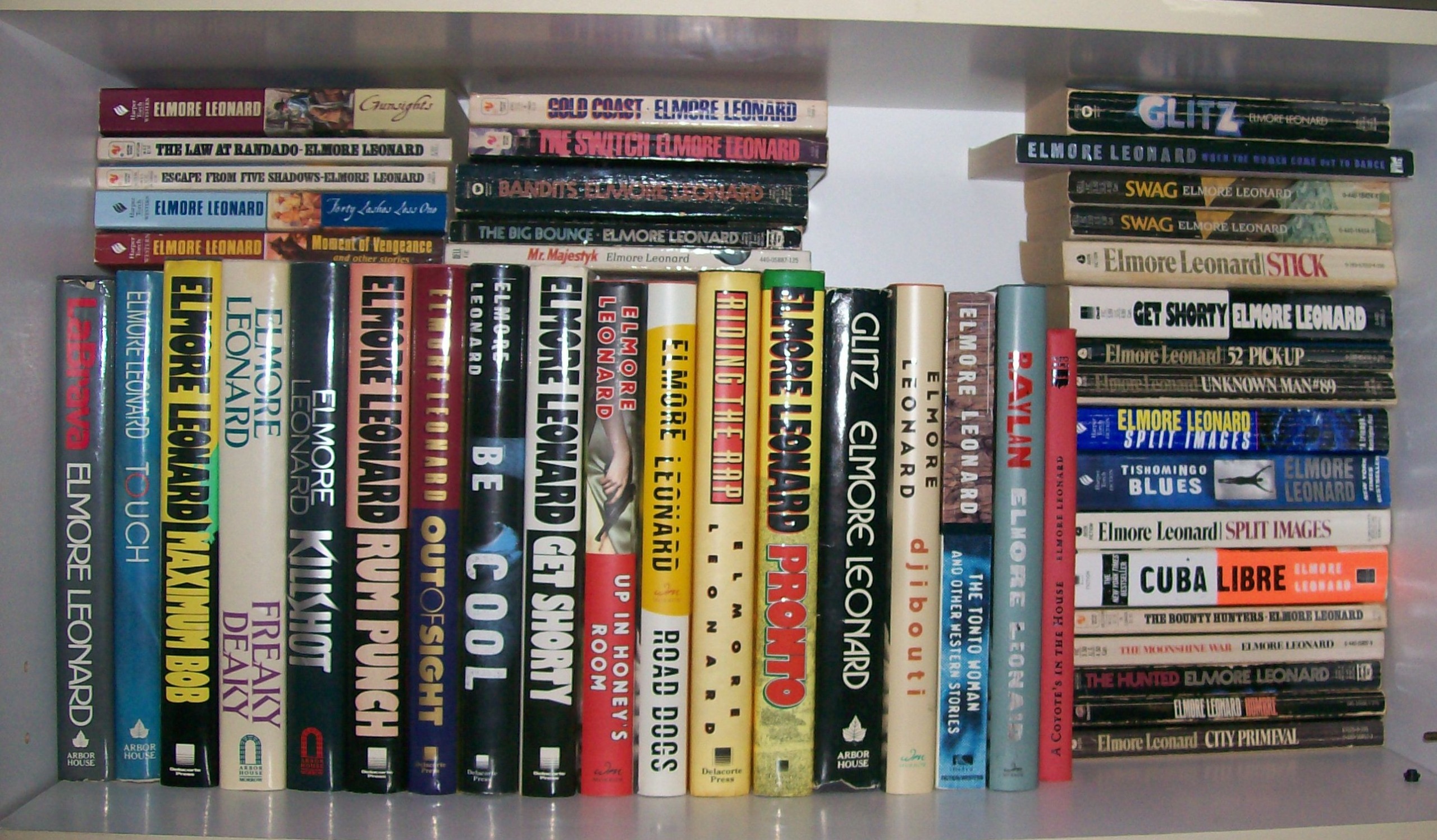

Like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler before him, Ross Macdonald was not a mystery writer; he was a serious novelist who wrote about murders and invented a detective to solve them. And while his plots were frighteningly complex, they were not the centre. People mattered, not puzzles. Archer never broke a case by sniffing fragments of a Florentine vase. He faced people, made them face themselves, made them suffer for their crimes and absorb much of their pain.

The more I learned about Macdonald, the more I realized he was everywhere in his books. He was Archer, commenting on the world around him. And he was many other characters and they were him. He breathed into them, bled with them, and the pain of his life had voice when Archer’s witnesses spoke of their own.

He was born Kenneth Millar in San Francisco, 1915. When he was three, his parents separated and his mother took hi to live with relatives on the poor side of London, Ontario. He was schooled in Kitchener, Winnipeg, London and Toronto. To support his wife (the novelist Margaret Millar), he wrote verse and sketches for Saturday Night.

All through his long exile, his mother reminded him he was American, a Californian. A bedtime fairytale for a lonely boy. A fellowship at the University of Michigan finally brought him home and he completed a PhD in Literature under the poet W.H. Auden. After a wartime stint with the U.S. Navy, he returned home to California to write full time.

He took the pen name Ross Macdonald and wrote a dozen books in as many years. The prose was that of a honed and gifted writer but the stories were overboiled, peopled with thugs, gamblers and molls. A tough, flip Lew Archer was beaten and blackjacked daily.

The territory had worked for Chandler and Hammett in the Twenties and Thirties, but it clearly wasn’t his. “I was writing my own books,” he said later, “but I wasn’t writing about my own life.”

His breakthrough came in 1957, when he and Margaret moved near his birthplace n the Bay area. It proved to be the epicentre of a psychic eruption. “My half-suppressed Canadian years,” he wrote, “my whole childhood and youth, rose like a corpse from the bottom of the sea to confront me.”

He laid Lew Archer aside and began a “serious” novel based on the Oedipus legend, about a boy exiled for the sins of his father. Neither of two drafts got past the thirteenth page.

In an essay on crime writing, Macdonald later wrote that the literary detective was “a kind of welder’s mask that enables us to handle dangerously hot material.” Shelving Archer had been a mistake. With the private investigator as narrator/mask, the story burst out over the winter: The Galton Case. It told of a young boy raised by relations in a poor area of Ontario, who appeared to be the lost son of a murdered man and heir to a massive fortune. Evaluating the boy’s claim, Archer notes: His voice seemed to have the resonance of his own life behind it.”

So at last did Ross Macdonald’s.

The Galton Case (1957) was considered Macdonald’s literary breakthrough.

In the 25 years from The Galton Case to his death this summer, the novels grew richer, ever more resonant. Children were abandoned, traumatized, often witness to the murder of a parent; crimes were committed to keep older crimes buried; families split under the groaning weight of secrets; fathers were stricken by their runaway daughters, as was he; the sins of the father were visited on the son.

Throughout his work, people desperately suppress their pasts; Archer digs them up. He is their relentless mirror, and all along the California coast, the corpses keep rising from the bottom of the sea. He solves cases with compassion and insight; the blackjacks all but disappear.

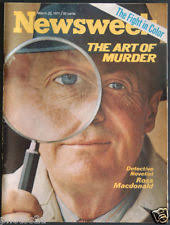

Many post-Galton books were national bestsellers (The Underground Man, The Goodbye Look, Sleeping Beauty, The Blue Hammer) and hailed by critics as modern American tragedies. Macdonald has been the subject of a Newsweek cover story and doctoral theses. The New York Times called the Archer books “the finest series of detective stories ever written by an American. In a Sunday Times review, they later dropped the reservation and called him, simply, one of the best American novelists now operating.”

In just a few hours I will meet him and tell him that I, too, intend to write detective fictions that belies the limits of the genre (this doesn’t seem self-conscious at the time). He will ask me to stay at the Via Esperanza as confidant and secretary. Father and son, we will forge his works.

***

I wake to sun streaming through white chintz curtains. Since when does L.A. sun cut through L.A. smog by seven? I slam out onto the catwalk in m jeans, startling the elderly Japanese man raking the night’s dead leaves from the parking lot.

“What time is it?” I call.

He leans over his rake to peer into the office window. “Nine.”

I fly bare-chested down the stairs and sweep into the office. The night clerk’s younger brother stares at my red eyes.

“It’s nine o’clock!” I thunder.

He glances back at the clock and agrees.

“What happened to my wake-up call?”

He looks at the empty peg board on the wall. “No messages.”

“I see that, damn you. I’m supposed to meet Ross Macdonald in Santa Barbara in three hours.”

“Better hurry,” he advises.

“It’s your fault. I left a message. I paid fourteen bucks just so I could woken up at seven.”

“My brother comes in at eleven. You ask him.”

“I’m asking you! Why didn’t I get my wake-up call?”

The office door opens. The old man stands there inquiringly. He looks at his son and at me and points to the top right drawer of the desk. He son opens it slowly to its full length and hands the old man a spool of plastic tape. The drawer stays open and the nine a.m. sun beams off a well-kept .45. His hand rests on the rim of the drawer.

“I’m willing to consider a refund,” I say.

His hand doesn’t move.

I sum up. Bowing out, I tell them their country fought bravely in the war.

“I debate kicking in the TV screen but he’d

hear me and drill me right through the ceiling.”

Back in my room, I stuff The Galton Case and both their towels into my pack. I debate kicking in the TV screen but he’d hear me in the office and drill me right through the ceiling. I settle for dumping the ashtray on the white bedspread.

Rage gets me to the Hollywood Boulevard car rental place by 9:30. With only one couple ahead of me, I can still be on the highway by ten. Oh no! It’s a honeymoon couple, and the clerk is outlining every bend in the road from Yosemite to Disneyland. When the lovers finally beam out, I all but grab his tie: “Anything that moves!”

When the carcinoma-grey Horizon hits Highway One, I have less than two hours to make 94 miles, find the restaurant, park. I change lanes restlessly as L.A. sprawls into Oxnard’s industrial parks. Californians drive like they’re in hot tubs. The Quebec driver in me surges. I stand on the gas and herd mellow commuters aside. J’passe a gauche. J’passe a droit. J’passe au but!

It’s only quarter to twelve when I make out Santa Barbara on a distant sign. Then I can read the small print: Next Twelve Exits. Damn! I gamble on the first. I swing into a gas station off the ramp and a mechanic rolls out from under a ’66 Dodge to look at my notebook. El Cielito, La Arcada, n. Mus. I haven’t looked at it since the day I talked to Macdonald and I can’t remember which is the restaurant, which is the street.

“Don’t know about the museum, never been,” the mechanic says. “But that first road there is El Cielito Drive. Starts right here and goes up the canyon so maybe it’s just up there.”

By noon—the lunch is now underway—the houses have thinned out to brush jutting out from the tangled canyonside. Even Californians wouldn’t put a museum here. There! On the right! A two-storey concrete structure. . . a fire station. Now about that? Up in a canyon, a fire station, not a museum. U show a fireman the notebook.

“The museum’s right in the centre of town,” he says, as though I were dense to think otherwise.

“Is there an El Cielito Street there?”

“Nope.”

“There’s an El Cielito restaurant,” another firefighter says. “Right back of the museum in La Arcada Court.”

***

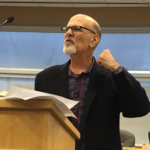

About thirty men and women are well into their meals at a long banquet table in a back room at El Cielito. There are no empty seats and my nerves shrill until the waiter adds on a table and seats me at what is now the head. I order a double Scotch and a cheese omelet. I’ve been eating the lining of my stomach since nine a.m.

The man on my right, about seventy with one blue eye gone milky, introduces himself as William Campbell Gault. I know the name. Macdonald’s The Blue Hammer is dedicated to him. An effusive man, he talks in a salty growl while I scan the room of writers.

The one I want doesn’t seem to be here.

I’ve seen just one photo of him, on the back cover of a book. In that photo, he seems more Archer than Macdonald. A snap-brim pulled low obscures the right eye; the left looks out at you and knows you. The face is fleshy, solid. Robert Mitchum as Kenneth Millar as Ross Macdonald as Lew Archer.

I’m about to ask Gault about him when I spot him halfway down the left side of the table. Is it? Yes. . . but hardly the man I was expecting. Balding, silver wisps across a high dome. Skin drawn tight around the mouth and cheeks. None of the solid comfort of the photo.

He eats quietly, listening, not talking. A manila envelope and tweed deerstalker sit on his lap, as though he wants nothing of himself to show at the table. Deer like, poised to flee. How to approach him? As Mr. Millar or Mr. Macdonald?

Wait. Eat. Calm yourself. After the meal. . . .

Bill Gault has never had real success but

neither has he had to do anything but write.

The omelet comes and goes in a blur, followed by most of the rolls from two bread baskets. Gault talks about his career: sixty novels, three hundred stories (mystery, boys, racing, romance). He has never had real success but neither has he had to do anything but write.

I listen and keep an eye on Kenneth Millar. Yes: Millar, not Macdonald. I prepare: themes, images, characters; why and how they touched me—my father left me too, I know how that is, you’ve never had a son—and as my mouth works on a dinner roll and my ear hangs on Gault, I see a movement halfway down the table.

He is pushing away, clutching his envelope and hat, nodding to those nearby, turning, leaving the dining room. I back out of my chair, leaving a roll and Gault’s sentence unfinished. I catch Millar by the bar outside the banquet room.

“Mr. Millar.”

He turns to look at me, cool and neutral.

“I called a couple of weeks ago.”

“Oh, yes.”

“You’re not leaving.”

“I have to. I’m sorry.”

“I thought we were going to talk today. If you knew what I went through to get here. . . .”

His look says he doesn’t really want to know. “Why don’t you come back in two weeks?”

It all wells up and out: “They didn’t wake me and the guy pulled a gun and I got the restaurant mixed up with the canyon road. . . .”

“I really do have to go now,” he says, apologetic and uncomfortable.

I can’t keep him. I take The Galton Case from my pocket. “Would you?”

He smiles at me, at the book that meant so much to him. He takes out a pen. I tell him my name but with one scratch the pen is dry. Neither of us has another. I should get one but I stand there staring. Millar, holding the hat and envelope against him like a shield against my glazed hysteria, walks to the bar for a pen. Idiot! Get him a pen! But he is coming back sand he writes in the book with the nub of a pencil from the bar. We stand there. I want to apologize for making him go get it, for anything for which he’ll forgive me.

“Thanks,” is all I mumble.

At the height of his fame, when the Underground Man came out in 1971.

“Come back in two weeks,” he says kindly. “Maybe there’ll be more time.” He turns and angles his tall frame between two chairs and is gone.

***

I returned two weeks later but he didn’t attend that lunch and then I left Southern California. I never saw or spoke to him again. I wrote to the Via Esperanza, detailing my adventures of the day, but received no reply.

I did become friends with William Campbell Gault. After Millar left El Cielito, we talked on and I followed Gault home in the grey Horizon. I had a book on Chandler that he had been looking for and in return he gave me hardcover editions of three of his novels and a paperback of Don’t Cry for Me, 1952’s Edgar winner for Best First Novel.

We spent the after noon talking of Millar, Chandler, writing, Canada, newspapers, unions: anything his quick mind lit on. Delightful, everything I’d dreamed of: the young writer and the old lion, the careful passing of secrets. But Gault wasn’t Millar; my fantasy was rooted.

A fantasy—confidant, secretary, pseudo-son—that would never graft onto the serious man named Millar who hid behind Macdonald who hid behind Lew Archer.

I came away with what I already had: a love for his talent and his books. That and a memento on the title page of The Galton Case where, beneath the false start of the pen, is written: To Howard, with good wishes and regrets, Ken Millar (Ross Macdonald).