Review by Howard Shrier

Howard Shrier

National Post, August 19, 2017

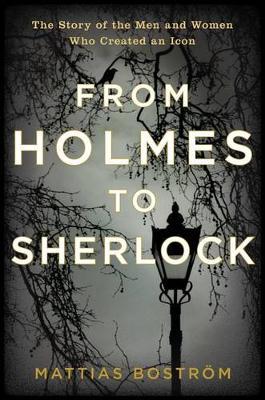

What would history’s greatest fictional detective make of From Holmes to Sherlock, by Swedish author Mattias Boström?

A self-described “active Sherlockian for nearly 30 years,” the 46-year-old traces the arc of Holmes’s popularity from his first appearance in Beeton’s 1878 Christmas Annual to the recent British TV hit starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, which moved Holmes and Watson from their Victorian trappings into the 21st century.

The first third moves briskly enough through the fascinating life and times of Holmes creator Conan Doyle, a man of singular intelligence and drive, with demons he came by honestly.

Conan Doyle was born in Edinburgh to Mary Foyle and the noted artist, depressive and alcoholic Charles Altamont Doyle, who died in an asylum. At the Edinburgh School of Medicine, he trained under Dr. Joseph Bell, who amazed his students with an uncanny ability to correctly diagnose ailments through observation, analysis and deduction.

Conan Doyle opened a medical practice in Portsmouth, eventually specializing in ophthalmology, and likely would have remained there had he not begun writing stories about a man who was a scientist, athlete and advocate, and who endured the same bruising episodes of depression he did.

Boström takes us through the publication of Conan Doyle’s first non-Holmes story; his marriage in 1875 to Louise Hawkins, who bore two children but died young of tuberculosis; his second marriage to Jean Leckie, which produced three more children; and his rise through English society as Sherlock Holmes grew into the first-ever worldwide multimedia phenomenon.

Holmes’s impact in his first decade or two cannot be overstated. He was more than the James Bond of his time: He was Bond, Batman, Superman, the Justice League and the whole damn Marvel Universe. His monthly adventures were eagerly awaited by crowned heads, presidents and literary luminaries. His death at Reichenbach falls was widely grieved, and his resurrection years later – when Conan Doyle needed money to maintain his baronial lifestyle – was resoundingly cheered. Writers for generations to follow generated pastiches and homages. Pirated translated editions flourished throughout Europe.

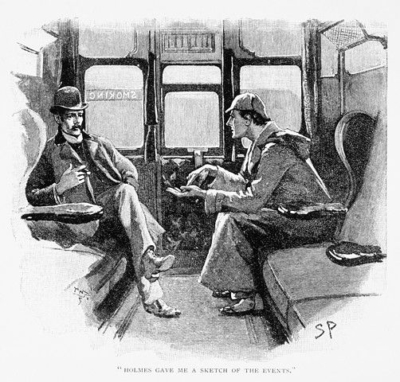

Illustrator Sidney Paget created the look of Holmes we all know: a gaunt figure in cap and deerstalker.

As Boström shows, the detective’s enduring image as a gaunt figure in deerstalker and cape was cemented in people’s minds by great illustrators such as Sidney Paget and actors such as William Gillette and Eille Norwood. Silent films were followed in Conan Doyle’s lifetime by talkies, including the hugely successful series starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce.

Boström is best when writing about Conan Doyle – a fierce advocate for justice who personally exonerated two innocent men precisely as Holmes would have done – and the love/hate relationship he had with the detective who would not stay dead.

It’s also fascinating to see what each subsequent generation wanted from Holmes as well as Watson – never forget Watson and his humanizing influence – and what writers, directors, producers and stars tried to give them.

- A Holmes who takes on the British aristocracy? Christopher Plummer in Murder by Decree.

- One who indulges his cocaine habit? The Seven Percent Solution.

- A novel about an aged beekeeper who solves a mystery? Choose from Michael Chabon (my vote), Mitch Cullin and Laurie R. King.

- A ripped action hero who boxes and practises martial arts, as did Holmes? Robert Downey Jr. is your man.

- Something for the kids? Spielberg’s Young Sherlock Holmes.

- A contemporary pairing of a man and woman in New York? Elementary, on CBS.

But despite its comprehensiveness, three critical weaknesses undo Boström’s work.

The first is his decision to tell the story in “novelistic prose,” because his gifts as a novelist are meagre. There is a numbing sameness to his chapters, to the way characters are introduced, their identities coyly withheld until Boström is ready to tell you who they are.

And while his research is undoubtedly strong, he tends to focus on pet subjects, such as Mitch Cullin (why him and not the vastly superior Chabon?) and the exclusive, insular fan club known as the Baker Street Irregulars, of which Boström is a member.

Not that the BSI is unimportant, but the space it gets in this book – including a laughable “novelistic” chapter about its eventual gender integration – far outweigh its contributions.

Finally, far too much space is devoted to the lives of Conan Doyle’s sponge-worthy sons, and the endless legal battles they fought to live off his estate without ever having to work. Again, the information is important – they and their mother, Dame Jean, wielded tremendous influence over which projects were made and how – but these sections should have been condensed and told in a sharp narrative voice. By this point, Bostrom’s storytelling style has dragged until a reader’s patience feels sorely tried.

Thousands of books have been written about Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes since 1878. The Toronto Public Library has an outstanding permanent collection.

After reviewing the data, as was his custom, Holmes himself would recommend rereading the first three collections of stories Conan Doyle wrote after The Sign of Four; hunting down Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes; or watching Jeremy Brett (before, during and after his own terrible episodes of depression), Plummer, Downey Jr., Johnny Lee Miller, Vasily Livanov et al play the great detective.