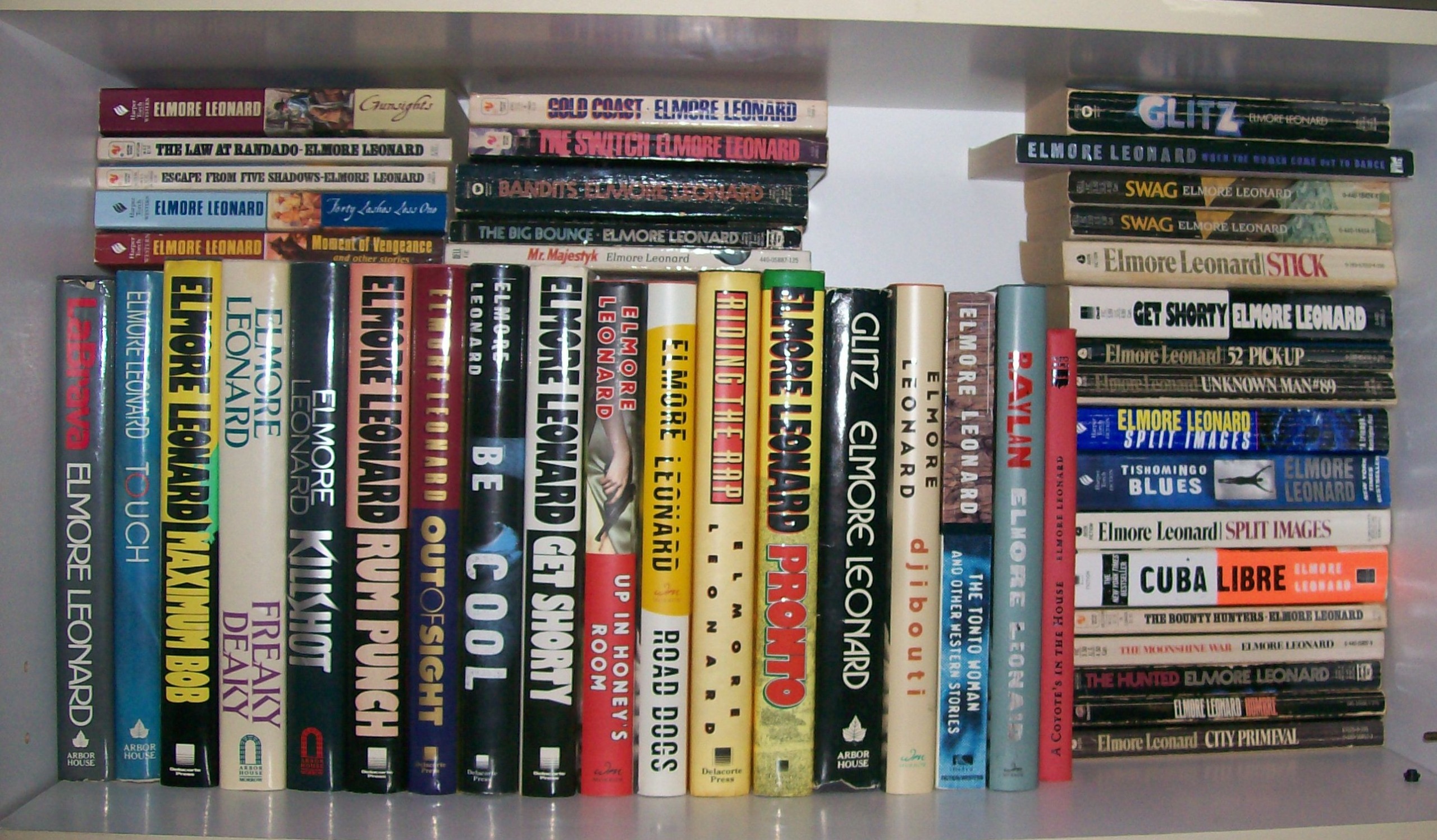

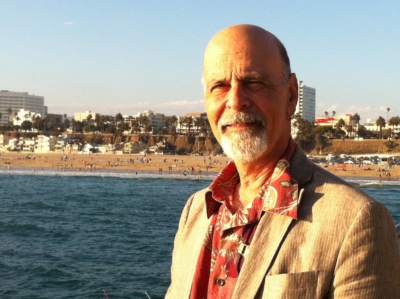

From a Toronto Star series on Lake Ontario called H2Ontario

On the waterfront: The Star took this photo for an essay it commissioned on Lake Ontario.

I spent the first half of my life in Montreal, an island city defined by the river that flows around it. Wherever you travelled, there were dark waters and bridges to cross: the Mercier, Champlain, Victoria and Cartier, which took you over the St. Lawrence, and our particular hell, the Pont Lachapelle, which crossed into Laval where I grew up. It was then one lane each way, always backed up, its approach from the north notoriously treacherous in snow.

I then spent a year in New York, cut off again from the mainland, this time by the Hudson, East and Harlem Rivers, with a dizzying variety of bridges and tunnels to cross over or under them.

In 1984, I came here, to a city defined not by rivers but a lake. Toronto had an actual end to it. The vastness of the lake, the openness around it — there was nothing like that on the crowded islands I had known. This was water that couldn’t be crossed by a bridge or tunnel. There was no mainland, no Jersey across the Hudson. If you wanted to drive to Niagara-on-the-Lake or Buffalo, there was only one way to go: the long way around.

I grew to like the Beach, and jumped early on at a chance to move to Woodbine and Gerrard, walking down most days to read the paper by seemingly pristine water. It was disturbing to learn how badly polluted it was then. Again I was near water I couldn’t swim in. I met some people who sailed on the lake and whenever I returned from an outing, I took as long a shower as my tank would allow.

As I came to know Toronto better, I discovered lovely island beaches where you could swim more safely. And the Martin Goodman Trail, the Leslie Spit and other urban oases that offered great access to the lake. My wife, who grew up near the ocean and loves open water, would live in the Beach if not for the prices and traffic, and takes the kids there as often as she can.

“There is a darker side of the lake that I have come to know over the years”

I spent more than 10 years working at the very edge of the city, on Lake Shore near Yonge Street, more days than not walking along the water at lunch to smooth the edges off corporate life — except for the days, and there were many, when the wind off the lake was so harsh, so cutting, it was worth staying inside and eating cafeteria food.

But there is a darker side of the lake that I have come to know over the years.

One of my first jobs in Toronto was to research Marilyn Bell’s swim across the lake for a film proposal. I spent days reading microfiche accounts of her epic battle, the giant swells that battered her, the harsh water that coursed into her mouth, the huge eels that bumped up against her. These have always remained primary images of the lake for me, no matter how pretty the water looks and how gently it laps at the shore.

As I researched the Ontario mob for my first novel, Buffalo Jump, I learned about the bodies of gangsters sunk in various harbours. And the bodies Lake Ontario continues to claim today: the murder victims, drowning victims, victims of domestic abuse, boating tragedies, suicides and alcohol-fuelled misadventures.

Yes, it has sun-splashed beaches and paths and a boardwalk full of walkers, runners, bladers and bikers, volleyball players, Tai Chi masters and the usual retrievers and labs that are better at Ultimate Frisbee than you or I.

To a congenital worrier, it is also a place where children are swept off the rocks of Ashbridge’s Bay. Where young men fall to their deaths from the Scarborough Bluffs. Where they topple into calm water three feet from safety after tripping on acid at a concert. Where June waters can be cold enough to claim a teen’s senses, where the bodies of women bearing marks of violence tumble and spill onto shores to await recovery and identification.

An even darker side — and much darker crimes — emerged as I researched my second novel, High Chicago, the story of a luxury condo tower going up near the lake on land that is wretchedly polluted. I scouted the area for weeks and much of what I saw was a wasteland unworthy of this city. A landscape of derelict buildings and heavy industries that so tainted the land over the years, the costs of reclamation and reuse are astronomical.

My research trip to Chicago showed how a city can provide unfettered access to its lakeshore and how far behind Toronto sadly lags.

When I began working at Yonge and Lake Shore in 1995, there was talk of tearing down the Gardiner and reclaiming the western Donlands. Some of that has been achieved. Some of it is still talk.

For decades we allowed sections of our lakefront to be abused and exploited, and it will take a great effort by all levels of government to undo the damage and bring us closer to the lake, as Chicago has. I hope they do it. Because whatever Lake Ontario is to me — a city’s edge, a place of calm, a source of occasional worry, a setting for a book — it is something unique to all of us and we all deserve to have our vision of it protected.

Because whatever dangers lurk in the mind of a crime writer, whatever eels slither through its cold depths, whatever waves capsize boats or snatch someone’s child away, whatever toxins have leached into the soil near its shores, there is more light in Lake Ontario than dark.

https://www.thestar.com/news/insight/2011/07/15/h2ontario_it_was_a_dark_and_stormy_lake_.html