Repairing the World, One Case at a Time: Howard Shrier’s Miss Montreal

Shlomo Schwartzberg, criticsatlarge.ca, July 17, 2013

Jonah Geller is back in Howard Shrier’s Miss Montreal (Random House Canada), the fourth book in his series chronicling the adventures of the determined Toronto private eye. Over four novels, including Buffalo Jump (2008), High Chicago (2009), Boston Cream (2012) and now Miss Montreal (2013), Jonah has gone from working for a security agency as a PI to running his own private investigative business, World Repairs, with partner Jenn Raudsepp. (World Repairs is the English term for the Hebrew phrase Tikkun Olam, a Jewish mandate to repair the world and make it a better place by doing good deeds. Or as Shrier puts it, “Jonah Geller: repairing the world, one asshole at a time.”)

Unlike other Jewish detectives, such as fellow Torontonian Howard Engel’s Benny Cooperman, in a series set in small town Ontario and a bit lighter in tone or Harry Kemelman’s low key Rabbi David Small books, Jonah is a tough guy: ex-Israeli army, with an exterior that doesn’t countenance any belligerence, including dealing effectively with anti-Semitism, evident in Buffalo Jump when he dispatched a bigot aboard a Toronto streetcar. He’s also something of a tragic figure, saddened by what he witnesses around him and more and more forced into situations where he has had to use violence, something he would rather have put behind him after a calamitous army experience in Israel.

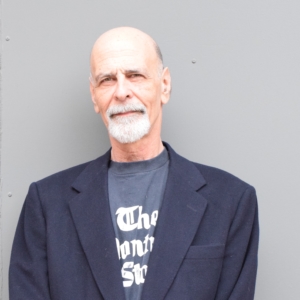

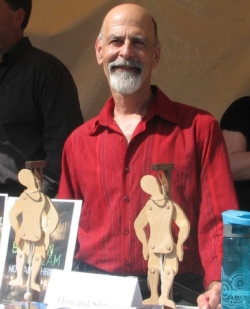

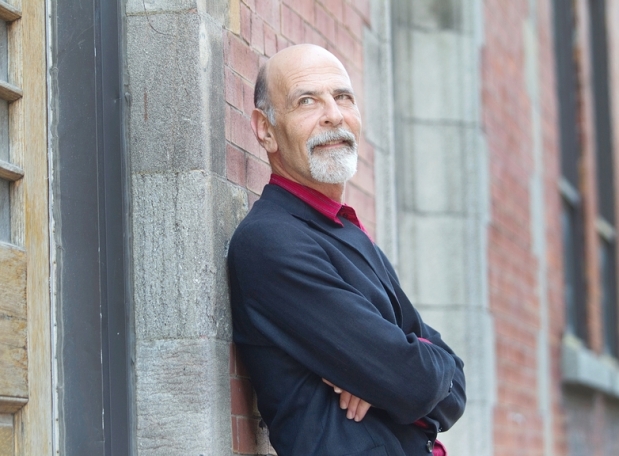

Shrier’s books are consistent in tone and depth, smartly written mysteries that rarely telegraph where they’re going and offer up some interesting regular characters, including openly gay Raudsepp and Dante Ryan, a hit man with a conscience. (I know Dante sounds like a cliché but in Shrier’s skilled hands, he’s not.) Shrier, who is a two-time winner of the prestigious Arthur Ellis award for excellence in crime fiction (Buffalo Jump won for Best First Novel of 2008; High Chicago for Best Novel of 2009), also brings his book’s settings, the cities where their stories largely unfold, to vivid life, as well.

They range from a down-at-its-heels Buffalo, whose glory days, if they ever existed, are behind it, to confident and corrupt Chicago to gentler Boston, riven by racial and religious currents as well as differing police jurisdictions. Miss Montreal, which begins with Jonah investigating the death of a Montreal newspaper columnist whom he knew from summer camp when they were both twelve, deftly focuses on Canada’s most unique city, dealing with its perpetual nationalistic French-English divide, current immigration concerns including integrating a sometimes hostile Muslim population as well as hearkening back to the city’s storied past, which was both wide open, in terms of illicit entertainment, and conservative in its social mores. (Shrier, now 56 years-old, began his writing career in 1979 as a crime reporter for the sadly defunct Montreal Star so he knows whereof he writes.)

It’s another ambitious but successful book, proof positive that Shrier is one of the finest mystery writers extant. Critics at Large recently interviewed him by email in his Toronto hometown.

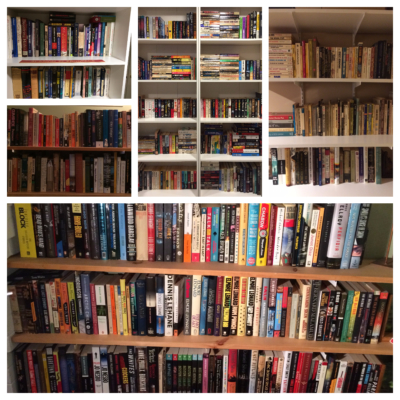

First thing I tell my writing students is read more. Read everything about anything. You never know what your characters will need to know.

Shlomo: What made you decide on a Canadian city as the centrepiece for the latest Jonah Geller novel? And can we expect a Toronto-centric book in the future?

Howard: In this case, I think Montreal chose me more than I chose it. I thought I had exhausted the American angle for now but I still wanted Jonah to have that fish out of water experience, so sending him to Quebec in the middle of an election campaign, amid its largest nationalist festival, tracing threads into the Muslim community made sense. Plus I was born and raised there, grew up on its stories and mythology, and thought it was time to mine it myself.

As for Toronto, who can say? I’d like to set a book here, whether it features Jonah or someone else. There’s enough grit and dirt to whet the blade of any crime writer. Right now, I’m staying with Montreal for a standalone novel set in 1950. More on that later.

Shlomo: It seems that Jonah is getting tougher and angrier as the series progresses, his hunches are sharper, his confidence more fine-tuned and his instincts better. Is that a deliberate character progression for you? How do you think Jonah has changed since Buffalo Jump?

Howard: It’s very deliberate. My conception of Jonah from the start was that he would not be the broken-down, bitter, alcoholic prototype. There would be a youth and freshness about him, a naiveté that would be lost through his experience with Dante Ryan.

As each book drew him into more violence, and sometimes loss, I couldn’t help but make him tougher and darker. Letting him keep that freshness and unblinking eyes would have demeaned the ordeals he and those close to him go through.

Shlomo: It is notable, I think, that it is in Miss Montreal that Jonah experiences real anti-Semitism for the first time, and it is also referenced through other character’s experiences such as Arthur Moscoe. (He’s the man who hires Jonah to probe into the murder.) Is this, as well as the acerbic commentary on the linguistic prejudices and treatment of immigrants in Quebec, a reflection of your disappointment in the province, since you like me are an anglophone who didn’t feel he could make a living there or chose not to do so?

Howard: When I left Montreal in 1984, I was trying to make a living as a writer and actor and the opportunities simply weren’t there. I didn’t leave with any real bitterness, because I spoke French fluently and could run my life in it. I just wanted a bigger pond to swim in.

That said, the subsequent waves of linguistic follies that follow every time a [separatist] Parti Quebecois government has been elected (not to mention the Liberal administrations of Robert Bourassa and others), have disappointed me deeply. Luckily for me, such a wave rolled in as I was researching the book and it provided ample grist for my satiric mill.

“If you put Rabbi’s David Small’s soul into Travis McGee’s

body, you’d have the perfect Jewish detective”

Shlomo: I like the messiness of your books in that good people die and not everything is wrapped up neatly in a bow as in other mysteries. Jonah has some of the world weariness of John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee but with a sadder, Jewish twist. How did you decide to approach Jonah as a Jewish detective? I assume you’ve read the Rabbi Small books and Benny Cooperman ones, among others, and went in another direction.

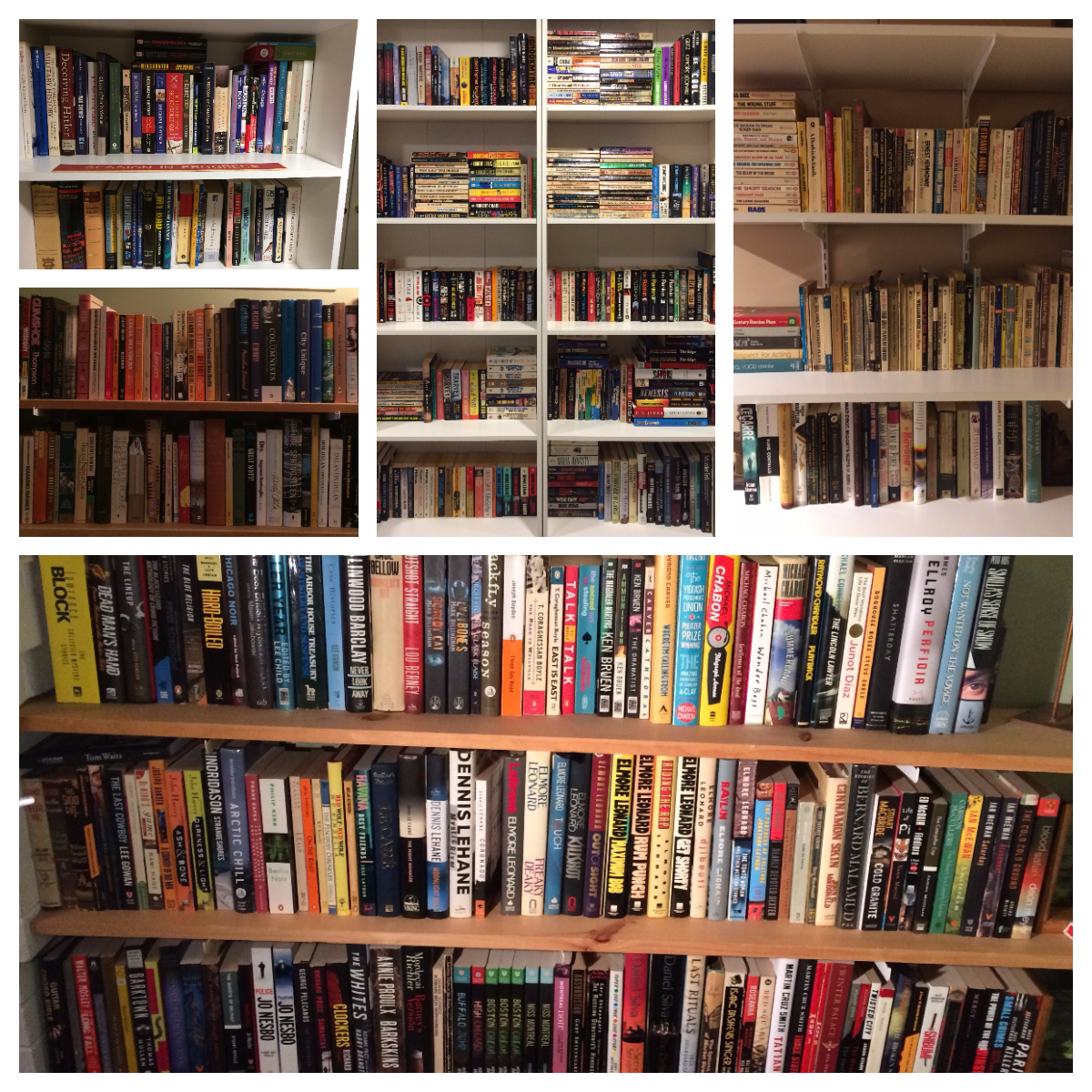

Howard: I loved both the Rabbi Small books and the Travis McGee series, every one of which I read. (In fact, if you put the rabbi’s soul into McGee’s body, you’d have the perfect Jewish detective.) I read a couple of Benny Cooperman books and admired them but did not feel influenced by them. The authors I really grew up on were Ross Macdonald and Raymond Chandler, then Robert B. Parker, Robert Crais and Dennis Lehane. Those PI writers have been a big influence.

But I have a Jewish voice and want to keep it and so I have also, over the years, devoured the works of Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, Mordecai Richler, Woody Allen, Isaac B Singer and many others. Braid them all together and that’s what I am going for.

Shlomo: Can we expect Jonah’s mother and brother to pop up in significant roles in a future novel? It would add immeasurably to fleshing him out further, I think.

Howard: Because the last two books spent so little time in Toronto, there wasn’t really a way to keep them in the story, other than in reference to Jonah’s legal status regarding further entry to the US. We’ll see what happens with them down the road.

Shlomo: You have a real knack for linking disparate stories and situations as Jonah investigates his cases and then blending them to perfection. How do you get your ideas, particularly since there are so many mysteries and detectives out there? How did you create such fresh takes on traditional, even potentially clichéd, characters such as hit man Dante Ryan or sidekick Jenn Raudsepp? For that matter, how did you seize on the idea of utilizing different cities as the impetus for your novels?

Howard: Ideas come to me through reading. I read all the time, whether it’s novels, magazines, websites, blogs. What happens next was best described by John Steinbeck. He said it was like he had a gelatinous plate in his head and of everything that flew through it, some things would stick. That’s how it is for me. I could read fifty news items on different web sites in one day and the one that says the number of organs available in China exceeds the number of prisoners executed there, which is the supposed official source, and it’s possible members of the banned Falun Gong sect are being killed and their organs harvested…. that one sticks and I start thinking, dreaming and reading about organ theft. And what better place to set a story about organ theft than the medical capital of America – Boston? That’s how Boston Cream came together.

I had the same experience with High Chicago. I was researching construction and development for a story set in the Toronto port lands, and Chicago is where the skyscraper was born. Where waterfront development was done brilliantly. To build in Chicago you have to be a master and that’s where I could find a bigger, more powerful adversary in Simon Birk. I had been there recently and liked it – Chicago has a lot in common with Toronto, plus plenty that’s purely original – and the city and the story made a perfect match.

(By the way, on the subject of all the other stories and writers out there: ironically, Elmore Leonard, perhaps my all-time idol even though I don’t write in his style, released his book Raylan on the same day Boston Cream came out, and about a third of Raylan centres on a kidney-theft ring. Just my luck…!)

Dante Ryan came to me fully formed. I knew him better

than I knew Jonah when I scribbled those first notes.

As for Ryan, he was fully formed from the start. His background became more specific as I researched and wrote the first book, but I knew him better than I knew Jonah when I scribbled those first notes. The hit man who can’t bring himself to do a job because the contract includes a child the same age as his young son. Once I knew that about him, he just burst into my room as he did Jonah’s.

Physically, Jenn was loosely based on a few women I’ve met, including a six-foot blonde Estonian (which Jenn is). Making her gay was an early choice, simply because I didn’t want the books to turn into a Moonlighting thing, will they or won’t they fall into each other’s arms?

Just my luck: Elmore Leonard’s Raylan came out the same day as Boston Cream, and also revolved around organ theft.

Shlomo: Unlike our late colleague David Churchill, who wrote copy for the LCBO (Liquor Control Board of Ontario), but chose to stay there and write fiction in his spare time, you took a leap of faith and left the LCBO to become a full-time writer . Has it turned out as you expected?

Howard: Things have turned out better than I ever could have hoped for in almost every respect. The books have earned rave reviews everywhere and a loyal base of fans in Canada. I’ve made some great friends in the crime writing community and it has given me the opportunity to design and teach mystery and suspense workshops at the University of Toronto School of Continuing Studies. I’ve had dozens of speaking engagements, readings, book signings where I have met readers and writers.

The only disappointment is that the series hasn’t been published in other countries. Random House Canada distributes them in the U.S. and they are available online around the world, but there haven’t been separate publishing or translation deals. Which mystifies me a little when I see some of the series that do get them.

Shlomo: What’s next for Howard Shrier? Another Jonah Geller novel or something else?

Howard: My next book is a crime novel set in Montreal, late 1950, when it was Canada’s unquestioned capital, financially, culturally and every other respect. The area north of Sherbrooke Street known as the Square Mile housed a hundred or so families, mostly Scottish and English, who controlled two-thirds of the country’s wealth through banking, insurance, shipping, railways and liquor.

Ste. Catherine Street was a glittering belt of nightclubs, bars, dance palaces, bookmaking joints. Glitz, glamour, gambling, guns – and that’s only the Gs. Not far away, on Ontario and DeBullion, were legendary brothels. Even rural Cote. St. Luc [where I grew up – Shlomo] was home to a huge casino.

New York mobsters were being driven out of their habitat by the televised Kefauver Commission inquiry into racketeering, and chose to escape the spotlight by shifting operations to Montreal, where Jewish, Italian and Irish mobs all had their piece of the pie.

There was also a surging tide of reformers battling vice in the city, led by the young Jean Drapeau (later Montreal’s mayor) and Pacifique “Pax” Plante. Montreal’s own Caron Commission inquiry into vice and police corruption had just been convened but had to shut down almost immediately because it had no budget for stenographers.

The story I am working on is a police procedural featuring two detectives – one English, one French – that bring all these worlds together, from the baronial halls of the Square Mile to the lowest depths of the sex trade. And that’s about all I can say right now.

– Shlomo Schwartzberg is a film critic, teacher and arts journalist based in Toronto. He teaches regular film courses at Ryerson University’s LIFE Institute and the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre.